Carbon offsetting: what it is and why it matters

Two cheers for an imperfect stopgap on the road to a low-carbon future

Slowing global warming by reducing carbon emissions and protecting natural carbon sinks is arguably the single most important challenge we face in the early 21st century. Carbon credits and the practice of carbon offsetting—compensating for unavoidable emissions by paying for the reduction or removal of an equivalent amount of emissions—play an important role in the transition to a low-carbon economy.

This post offers a plain english explanation of what carbon credits are and the role played by carbon markets.

The problem

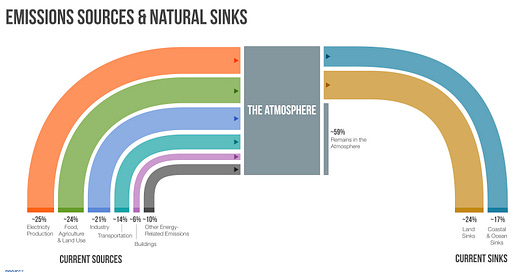

Every year, significantly more greenhouse gasses are produced than can be removed from the environment through natural means. As a result, the concentration of greenhouse gasses in the atmosphere has increased from 280 parts per million to 420 parts per million, which is the main driver of climate change. We urgently need to reduce that by about 50 billion tonnes CO2-e per year to slow climate change.

Both climate and the human activities driving climate change are complex systems, which are highly interconnected with feedback loops [but that’s the topic of another post]. The most straightforward analogy for the problem with this system is a bathtub. The bath is already pretty full, and every year more water is going in than is draining out. To work our way out of this situation, we need to reduce emissions going in, support the natural carbon cycle (the carbon sinks that drain emissions out of the atmosphere), while addressing the underlying drivers that created the situation in the first place.

This systems change has three high level indicators that we can target:

how fast emissions are entering the atmosphere (from carbon sources)

how much is in the environment currently, and

how fast emissions are being drained from the atmosphere (by carbon sinks).

Project Drawdown has created a great graphic to illustrate this, which shows that the emissions entering the atmosphere are more than double those that can be drained through natural carbon sinks. This makes it pretty obvious the main push should be on immediately slowing emissions by helping emitters transition to low and zero carbon production processes, while preventing the destruction of existing carbon sinks.

Unfortunately, the time we have to do this is quite short while transitioning technology and production processes can take time. In the short term, while we’re reducing emissions, the ability to offset emissions that can’t be avoided today by funding reductions elsewhere is very important. Offsetting creates a path to net zero for current emitters so that everyone can participate in shifting the global economy toward the low-carbon future humans need to limit global warming and avoid massive loss of human life within this generation.

Reducing the sources (of inputs of carbon to the atmosphere) is going slowly, so the next option is to increase the sinks, namely the uptake of carbon by natural processes. To use our bathtub analogy, if the tap can't be closed, then the next best way to lower the level of water in the bath is to pull out more plugs and make more holes in the tub.

Carbon credits are not perfect, and they are not a long-term solution. The purchase of high-quality carbon credits is useful as part of a credible pathway for companies to reach net zero in the short term through compensation of unavoidable emissions as they transition production practices, and economies grow capacity for and transition toward low-carbon alternatives like renewable energy, electric vehicles, sustainable food systems and highly circular production practices.

What is a carbon credit?

Carbon credits are tradable certificates or financial instruments that represent ownership of something in the real world, much like a stock certificate. In this case, each carbon credit represents the right to claim one tonne of carbon dioxide emissions that is either not emitted into the atmosphere or is removed from the atmosphere.

Much like a bundle of sticks tied together, property is ownership not of a single thing, but of a bundle of rights related to a thing that can be independently bought, sold or leased. These include legal rights to occupy, sell, mortgage, subdivide; rights to extract particular resources through water, forest products, grazing, or mineral extraction; rights to protect things like biodiversity, wildlife corridors, floodplains, or forest cover.

A carbon credit is a lease on a particular right: the right to sole claim over a tonne of carbon into the atmosphere in a given year. Those who emit carbon in their production processes (emitters) “lease” that right from someone who is avoiding, reducing or sequestering carbon from a scientifically documented baseline.

Each carbon credit is assigned a serial number in a publicly accessible emission registry when it is issued. These can be bought, sold and transferred like any other financial instrument but can only be used or “spent” once to offset one tonne of CO2-e emitted, after which it is permanently retired.

Carbon markets and projects explained

There are many ways to meet emissions reduction goals. Most countries are using market mechanisms to affect supply and demand through carbon credits. Carbon markets rely on on the basic market principle that quantity of a good supplied will rise with demand so long as there is a visible price that makes it financially viable for the supplier.

The goal of carbon markets is to use the demand for carbon credits (from emitters) to create and grow the global supply of activities that avoid, remove, or capture emissions. This works by creating a tradeable abstraction (the carbon credit) that emitters can purchase to pay for their emissions in a given year. These carbon credits are produced by carbon projects—projects reduce emissions and are compensated in carbon credits. Credits flow from carbon reducers to carbon emitters; money flows in the opposite direction, from emitters to reducers. Thus projects that reduce emissions are paid to operate by those emitters.

This makes it possible to finance the development of carbon projects that would not have been financially viable (and thus would not have happened) without the additional income from the credits.

These projects act in one of three ways.

avoid emissions that would likely have happened, for example replacing fossil fuel-derived energy with renewable sources.

remove emissions from the atmosphere by doing things that capture (sequester) carbon and store it in liquid or solid form, for example, planting more trees

capture greenhouse gases that would otherwise be emitted, to destroy or use for other purposes, for example capturing methane gas from wastewater.

Many carbon projects also deliver measurable co-benefits, or non-carbon outcomes that benefit society more broadly. They can include environmental benefits, social benefits, economic opportunities, and improved culture and heritage benefits for traditional owners.

Is it really that simple?

Yes and no. In theory, there is no difference between theory and practice. In practice, this difference can be substantial. This article is intended to lay out the basic theory on its own, to create shared ground from which to have discussions.